The American chestnut tree was nearly wiped out by a blight in the early twentieth century. At one time these massive trees comprised thirty percent of the hardwood canopy in the eastern mountains of the U.S. Decaying stumps and logs were what remained when I was a boy growing up in the Blue Ridge of Virginia.

Stumps and logs were what remained of the American chestnut tree on our farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains when I was a boy. At woods edge near the house stood a lone tree, stunted, no more than ten feet tall. For years it leafed out in the spring, but the leaves withered. Then, only sprouts sprang up at the base of the trunk. Our sheep nibbled the sprouts to the ground, and finally, the sprouts gave up, too.

It was with the American chestnut tree that my imaginative life began. Oh, I remember playing Hopalong Cassidy in my cowboy hat and cap pistols, or pretending my plastic Rin-Tin-Tin could bark. But when I moved to the farm at age six, I began to imagine another world altogether, a world that had vanished, leaving traces that were evanescent, too.

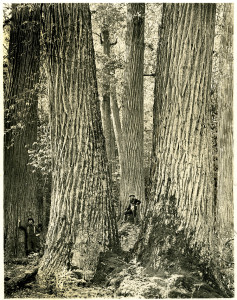

The chestnut stumps and logs were huge, twice the diameter of any standing hickory, poplar, or oak I found in my wanderings. And my great-uncle George Weddle told me stories about those living giants, how men with axes and crosscut saws had felled them by hand, bucking the saw logs on sleds drawn by yoked steers or teams of draft horses. He told me stories about chestnut mast so deep in the woodlands, farmers loosed their hogs to fatten for slaughter, how the hogs turned feral and the farmers hunted them with hounds, drinking moonshine from a jug on midnight chases.

By the time I was twelve the tack and harness for the draft horses hung dry rotting in the barn, along with broadaxes and two-man crosscut saws flaky with rust. Rod after rod of chestnut split-rail fences snaked along creek bottoms and ridgelines, though as time passed, the rails began to rot, and we sawed them for firewood. The new braided wire fences we built didn’t blow down in the March winds. And in my great-aunt Minerva’s house, there were straight-grained chestnut boards joined so tight you felt you were inside a tree.

Botantists have discovered ways to make the American chestnut tree resistant to the blight, and hikers still discover isolated stands untouched by the disease of a century ago. Sometimes I think about going to see those trees. But in truth, I prefer my imagination.

I see the forest I dreamed, scampering among gray stumps as a boy, filled with reverence and awe.