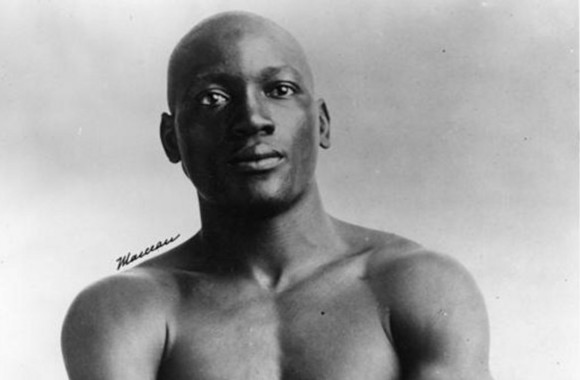

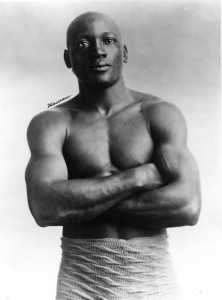

The son of former slaves, Jack Johnson became the first African American heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

Jack Johnson was the son of former slaves. When he defeated Canadian fighter Tommy Burns in 1908, he became the first African American heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

Johnson was a huge threat to Jim Crow. He was proud of his blackness, a magnificent physical specimen, and worse, attractive to women of all colors.

He enjoyed flaunting his success. He was a dapper dresser and drove expensive racing cars. He traveled in the company of white women, marrying three of them in his lifetime.

A succession of fighters, each called “the great white hope,” fought Johnson in exhibition matches. Johnson beat each one.

Promoters finally coaxed heavyweight champion James L. Jeffries out of retirement to fight him. Lauded for his strength and stamina, Jeffries had twice defeated highly regarded black boxers, the last one by knockout.

“I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a negro,” Jeffries said.

On July 4, 1910, before a crowd of 20,000 in a ring built just for the event in Reno, Nevada, Johnson and Jeffries joined the “Fight of the Century.” Johnson dominated, knocking Jeffries down twice. Jeffries’ corner threw in the towel before the start of the final round, fearing the former champion might be knocked out.

Race riots broke out in more than twenty-five states and fifty cities across America. Twenty people were killed and hundreds injured.

Jim Crow America wasn’t finished.

In 1912 Johnson was arrested for transporting the white woman who would become his second wife “across state lines for immoral purposes.” The case fell apart. He was arrested again, tried, and convicted. He fled the country to avoid prison. Seven years a fugitive, he surrendered to authorities and served a year in Leavenworth.

On June 10, 1946, angry at being refused service at a diner near Franklinton, N.C., Johnson sped away and crashed along Highway 1. He died in Raleigh’s Saint Agnes Hospital, the nearest facility that treated blacks.

Jim Crow’s victory was complete.

The prize fighter’s tie to the Virginia Christian story? Scholar Derryn Moten notes that Johnson’s Chicago attorney, William G. “Habeas Corpus” Anderson, traveled to the governor’s mansion in Richmond, Virginia, to plead for clemency two days before the girl’s scheduled execution. The governor listened politely, but remarked that Anderson was “ill-informed as to the facts of the case.”