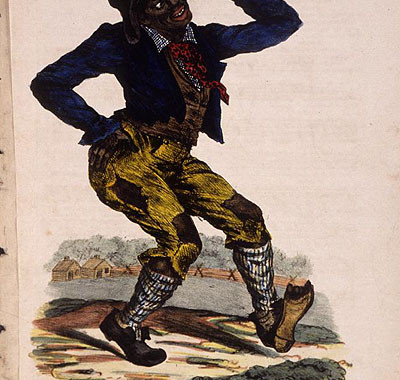

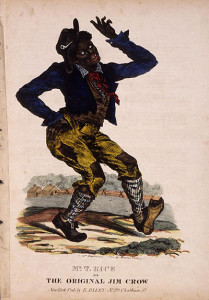

Edward Williams Clay (1799-1857) lithograph, cover to sheet music of “Jump Jim Crow,” a song popularized by American minstrel Thomas Dartmouth Rice about 1832.

“Jim Crow” is clothed in ambiguity and irony.

I first came across the term in a University of Virginia class. On the syllabus was C. Vann Woodward’s The Strange Career of Jim Crow, a series of lectures at the University published in 1955.

It’s likely there was a real, historical Jim Crow, an African American, or maybe an American Indian, who enjoyed singing and dancing. He might have worked in a horse stable, or maybe drove a stagecoach, or maybe worked on a riverboat dock.

Maybe he was old and crippled, hence his shuffle, or maybe he was young and hale, hence his tricky dance step. He may have performed in Cincinnati, Ohio, or Louisville, Kentucky, or Memphis or Nashville, Tennessee, or Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, or maybe even Baltimore, Maryland.

Whatever his origin, Jim Crow became legend through Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a traveling actor, who was a white man. Somewhere on his travels, Rice had observed a man he began to portray on stage as an African American, singing a special song and dancing a special step.

Sometime around 1832, the song and dance emerged as “Jump Jim Crow,” and became wildly popular among audiences in the United States and across the Atlantic.

Wearing burned cork blackface, Rice performed “Jump Jim Crow,” along with other songs, in the famous “Bowery” in New York. He later performed in Boston, Massachusetts, and in 1836, he even performed in London, England. Author Anne Grimes notes that his performances ran for 21 consecutive weeks, unprecedented at the time, and the minstrel performed his trademark song “1,260 times during this period.”

Rice’s ditty was on the lips of young and old, rich and poor, nobleman and commoner. Across America, England, and Europe, his stage caricature represented the stereotype white people held for black people of the time.

“In the popular imagination, blacks were primitive of culture and innately inferior of race,” writes scholar James Dorman. “The recurrent theme in the songs and the primary features of the stereotype are unquestionably the Negro’s irresponsibility, his child-like simplicity, and his eternal good humor…There is nothing in this happy, guileless, funny creature to be distrusted or feared.”

Just as Rice’s character Jim Crow was singing on the stage, a far different stereotype of the black slave would scream from headlines made in the fields of Southampton County, Virginia.

Next week: the Nat Turner insurrection of 1831.