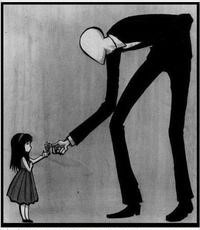

The Slender Man is an online boogeyman that has grown into a digital urban legend through photo-shopped images and reader-generated stories on websites.

American courts used to try children over the age of seven as adults. While they received the strict protections of a defendant in a criminal trial, they could also receive a court’s harshest penalty, death.

By the nineteenth century, attitudes had changed. The first juvenile court convened in Chicago, Illinois, in 1899. Procedures were more flexible, emphasizing rehabilitation, rather than punishment. Since the juvenile mind was unformed, it could be positively influenced, reformers argued.

Modern science supports that position—the part of the brain experiencing the most change during teenage years is the prefrontal cortex, where judgment and decision-making reside.

During the Virginia Christian murder trial, Commonwealth law stated that a juvenile could not be executed or imprisoned. Although there were trade schools to rehabilitate white juveniles, there was no such institution for colored girls. Funds had not been allocated.

Fast forward a century. Last week a judge ruled that two Wisconsin girls, Morgan Geyser and Anissa Weier, 13 years old, should be tried as adults for stabbing their girlfriend after a birthday sleepover and leaving her to die.

A Wisconsin law passed in the 1990s—when many state legislatures were getting tough on juvenile crime—calls for any child older than the age of ten to be tried as an adult for a serious crime, unless the presiding judge waives the requirement and sends the defendant to a juvenile court.

That’s right. Any child older than the age of ten.

The girls said they stabbed their girlfriend to impress The Slender Man, a mysterious, faceless online character said to terrorize children. When apprehended, they told authorities they were walking to northern Wisconsin, where they believed The Slender Man had a mansion in the Nicolet National Forest.

Weier has been diagnosed with a delusional disorder; Geyser with early onset schizophrenia.

Yet the judge determined that moving the girls’ trial to juvenile court would “unduly depreciate the seriousness of the offense.”

An argument for trying children as adults is deterrence—other children will shy away from committing similar crimes. No evidence supports this claim. Another argument is money. It’s cheaper to try a child in adult court, with none of the juvenile court expenses of counselors, psychiatrists, and rehabilitative programs.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, 23 states in the past eight years have enacted juvenile justice reform, removing children from adult criminal courts.

That’s a start.